Reverend Scott and the Stevensons by Lindy Perez

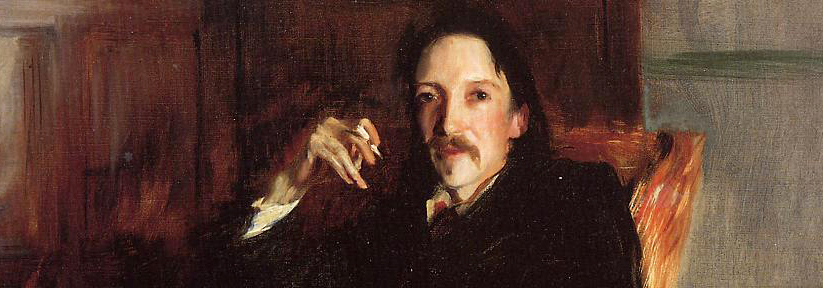

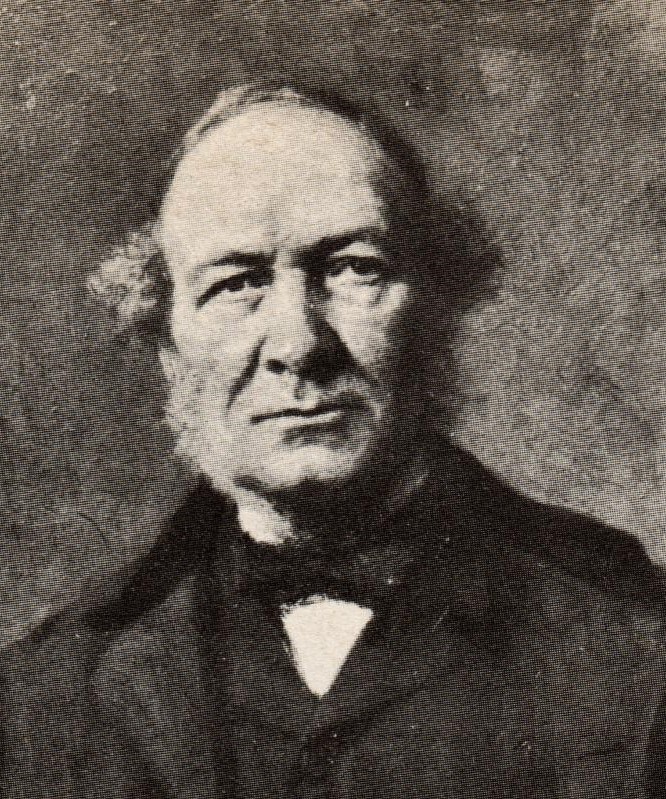

Reverend Scott

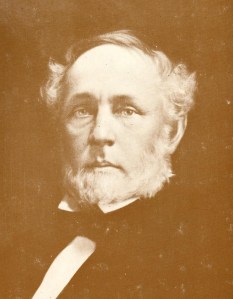

Thomas Stevenson, father of RLS

Dr. William Anderson Scott was the Presbyterian minister who married Robert Louis Stevenson and Fanny Osbourne on May 19, 1880 in San Francisco. I came across his name in a biography of another writer and was surprised that this man, out of all the ministers in the city, with his history, was the one chosen to marry them.

Did they know, for example, that Dr. Scott stayed loyal to the South throughout the Civil War? that he was southern by birth and culture and had owned slaves, which he freed just before moving to San Francisco in 1854? Had they heard that he was notorious for his views in pre-war San Francisco and eventually burned in effigy and driven out of the city in 1861 because he would not criticize the Confederate states for seceding or for slavery?

Fanny’s father, we remember, was a friend of the abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher, and her first husband had served in the Union Army. Louis embraced freedom, abhorred hypocrisy, and championed the underdog all his life. In The Amateur Emigrant, he recorded his first encounter with American Negroes and how impressed he was by the railroad porter who was strikingly different from the portrayal by Harriet Beecher Stowe, sister of Henry.

To satisfy my curiosity about “why this minister?”, I turned to a biography written in 1967 by Clifford Merrill Drury titled William Anderson Scott “No Ordinary Man.” My reading of the life of this complicated individual left me conflicted and saddened – why would someone with extraordinary abilities, virtues, and goals refuse to be on the right side of history? Like others at the time, he was blind to the immorality of slavery.

Rev. Scott returned to San Francisco after ten years in exile, was welcomed back by parishioners, and avoided controversy from then on. The war had ended 15 years prior, so perhaps neither Fanny nor Louis knew or cared about his background. It was Louis who chose Dr. Scott, presumably because he was a Presbyterian with Scottish lineage whose church stood in a familiar neighborhood. He may have heard that Rev. Scott was considered the most eminent minister in San Francisco at the time, an Old School Presbyterian, a conservative disciple of the Church of Scotland, much like Thomas Stevenson, father of Louis. As a university student, the younger Stevenson had rebelled passionately against his father’s religious orthodoxy. However, having suffered months of estrangement from his parents, personal uncertainty, and severe illness, Louis had finally received a cable from his father which promised a regular allowance and support for his marriage to Fanny. The eager bridegroom was in a forgiving and grateful frame of mind!

No doubt, Louis was strongly attracted to the elderly Rev. Scott, who was warm and genial, intelligent, well-traveled and highly educated. The two exchanged theological books at their first meeting: Scott gifted one of his own and Louis gave Scott his personal copy of Thomas Stevenson’s work “Defense of Christianity,” which he had carried throughout his travels. The senior Stevenson was a devout Calvinist and amateur theologian, aside from his engineering expertise.

It is more than likely that William A. Scott reminded Louis of his father. They were about the same age, had a similar broad build, and were popular personalities in their respective circles. Both harbored self-doubt and melancholy. Jules Simoneau in Monterey may have been the father-figure Louis wanted, while Rev. Scott was the father-figure he had.